Companies and industries that are out of favor tend to attract our interest. While we focus on franchise businesses with large moats and good management at a reasonable price, investing in cyclical companies has a certain appeal. After all, it seems straightforward enough that abrupt swings in market psychology will create bargains, even huge, screaming bargains. If you can enter the market at the “point of maximum financial opportunity,” big money can be made.

Source: Big Fat Purse

This general principle led us to take a look at a particularly cyclical industry, oil. The recent drop in the price of oil and the concomitant drop in the value of oil and oil-related companies caught our attention. We thought it was highly likely that the market was incorrectly extrapolating current oil prices far into the future and under-rating the likelihood of a return to high prices. This over-pessimism should lead to bargains in oil stocks.

In fact, as Howard Marks pointed out in a 2014 memo, the oil market tends to be self-correcting:

- A decline in the price of gasoline induces people to drive more, increasing the demand for oil.

- A decline in the price of oil negatively impacts the economics of drilling, reducing additions to supply.

- A decline in the price of oil causes producers to cut production and leave oil in the ground to be sold later at higher prices.

Marks concluded: “In all these ways, lower prices either increase the demand for oil or reduce the supply, causing the price of oil to rise (all else being equal). In other words, lower oil prices – in and of themselves – eventually make for higher oil prices.” Therefore, the current dip in oil prices and the corresponding dip in oil company valuations should be merely temporary.

Next, we decided to specifically focus on midstream master limited partnerships (MLPs). As midstream MLPs generally hold mature assets that require modest maintenance capital and generated stable cash flow, we saw MLPs as bond-like substitutes with high yields and very modest growth expectations. Such companies seemed attractive at the right price.

Boy, were we naïve! Walking into the cesspool that is the MLP sector was an eye-opening experience.

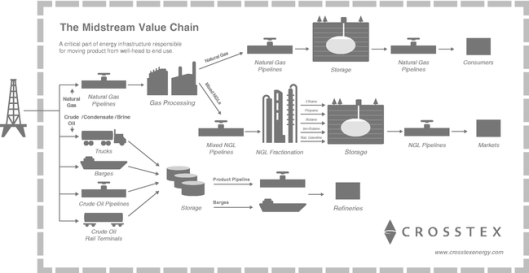

The Oil & Gas Value Chain

“Midstream” MLPs represent the largest single segment of the MLP universe. As the name suggests, midstream companies sit between upstream companies which actually extract the oil or natural gas and downstream companies which distribute the commodity. Midstream companies operate pipelines, storage facilities, and/or processing plants. These are predominately fixed-infrastructure assets designed to handle specific commodities and to provide transportation services in a specific direction. They charge toll-like fees to the producers for throughput on their infrastructure.

With the advent of large scale horizontal drilling roughly 8 years ago and the surge in hydrocarbons flowing out of Alberta, the Bakken, DJ Basin, Marcellus, Permian, Eagle Ford, et al, the US experienced a huge build out of energy infrastructure. Much of this build out took place via MLPs.

Attractive Features of Midstream MLPs

Our look at Midstream MLPs focused specifically on companies providing oil storage services. The MLPs that derive 90% to 100% of their revenue from oil storage fees are;

- Arc Logistics (ARCX)

- PBF Logistics (PBFX)

- VTTI

- West Point Terminals (WPT)

These companies have many of the characteristics we look for:

- Stable and Predictable Cash Flows – A number of mechanisms provide a substantial degree of security around future cash flows:

Limited Commodity Price Exposure – Although the MLPs operate in a highly cyclical industry, they are relatively insulated from the cycles because they do not take ownership of the oil at the terminals.

Volume Security – Many oil storage contracts contain minimum volume commitments (MVCs)

Long Term contracts – Typically contracts have two 5-year renewal terms and inflation-based cost escalators.

Customer Stickiness – Customers tend to stick around for a long time. The top ten customers for one storage MLP, World Point Terminals (WPT) have been with them for average of 9+ years

- High barriers to entry, including:

Limited locations that possess the requisite characteristics necessary to support an oil storage business, such as proximity to pipelines, refineries, processing plants, waterway, demand markets and export hubs;

the extended length of time and risk involved in permitting and developing new projects and placing them into service, which can extend over a multi-year period depending on the type of facility, location, permitting and environmental issues and other factors;

the magnitude and uncertainty of capital costs, length of the permitting and development cycle and scheduling uncertainties associated with terminal development projects present significant project financing challenges, which could be exacerbated by any tightening of the global credit markets; and

the specialized expertise required to acquire, develop and operate storage facilities, which makes it difficult to hire and retain qualified management and operational teams.

- Easy to Understand – Even we can understand owning a big tank and being paid to store someone’s oil in it.

Conventional wisdom suggests midstream MLPs are generally the most stable assets within the MLP landscape.

General Organization Structure of MLPs

Unfortunately, the conventional wisdom is wrong. Wall Street took these straightforward, boring businesses and put them in highly engineered structures. See below:

The key MLP stakeholders are:

- The “Sponsor.” The entity that forms or creates the MLP.

- The general partner (GP). Operates and manages the MLP.

- The Limited partners (LP). Simply provide capital

To further confuse things, the Sponsor frequently also acts as the GP and owns LP interests.

Sponsors are typically in the oil and gas field. They transfer certain assets (for example, pipelines or storage tanks) from the pre-existing business to the MLP. They then sell LP units to investors through an IPO.

The GP usually owns a 2% minority stake, essentially all the voting rights, and Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs). IDRs warrant the GP to receive an incrementally larger share of the distributions paid to unitholders as the distribution grows. It is common for IDRs to split distributions 50/50 between the LP and GP at the highest level of the distribution schedule (or “tier”), a condition known as “high splits.”

Once in place, Sponsors will transfer further assets to the MLP via transactions known as “dropdowns.” The Sponsor drops assets down to the MLP and takes back more equity in the MLP and/or debt.

The Power of Bad Incentives

MLPs are designed to attract retail investors with large and growing dividends while making sure the Sponsor maintains control over the vehicle and keeps their downside protected.

This design as well as MLP marketing creates four important forces:

- MLPs must distribute all available cash

- MLPs are presumed to maintain stable growth

- MLPS rely on funding from external sources

- GPs have high upside potential but little downside exposure

When these forces combine, the end result is a highly combustible substance.

- MLPs Must Distribute All Available Cash

MLPs are contractually required to distribute “all available cash.” In practice, available cash is essentially operating cash flow less cash interest expense and less maintenance capital expenditures. This sounds great on the surface. After all, many shareholders would be better off if CEOs effectively had all discretion over capital allocation taken away from them.

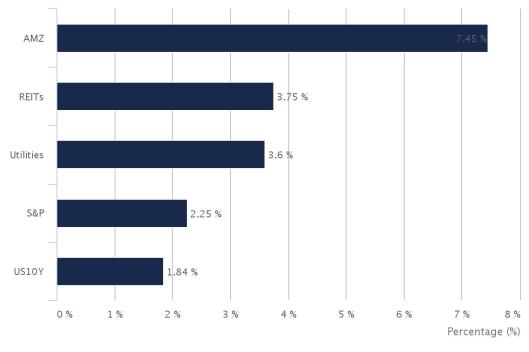

The high percentage of cash flow distributed leads to high yields. As of May 25, 2016, the Alerian MLP Index (AMZ) reported a yield of 7.45%. This yield is far higher than other asset classes as you can see below:

However, this high yield does not come without a price. The coverage ratio, i.e., the ratio of available cash to distributions paid, of midstream MLPs is just over 1.09x. This means for every dollar paid in distributions, there is a little more than one dollar of available cash to make the distribution. Contrast this with the more familiar dividend payout ratio – the ratio of dividends paid to reported earnings, typically associated with corporations. The aggregate payout ratio of S&P 500 companies is a bit over 32%. For MLPs, the comparable metric to the dividend payout ratio is the inverse of the coverage ratio. On that basis, one can see MLPs on average pay out nearly 92% of their cash flow in distributions. That leaves no ability to fund growth out of cash flow from operations. This high payout ratio raises a host of other issues discussed below.

2. MLPs Are Presumed to Maintain Stable Growth

Below is a typical slide from an MLP investor presentation showing hockey stick distribution growth.

Source: PBFX Investor Presenation

The pressure for an MLP to maintain a stable and growing DCF is much more intense than that of a normal company to maintain steady earnings.

The question then becomes, how do you fund this type of growth when almost no cash is retained?

- MLPS Rely on Funding from External Sources

Any capital to the MLP business must come from external sources. This is not a good position to be in. “(T)he ability to make accretive capital investments is largely dependent on others – a risky position that most competitive, strategic-thinking entities would rather not be in.” For one thing, should the capital markets largely dry up or become more expensive to access, the sources and rates of MLP distribution growth could be greatly reduced. For another, if the MLP comes to rely on debt, they can find themselves in a very awkward position should business turn down. If the MLP relies on equity infusions, minority owners suffer dramatic dilution.

- GPs have high upside potential but little downside exposure

IDRs entitle the GP to receive increasing percentages of the incremental as the MLP raises distributions to limited partners. Initially, the general partner receives only 0-2% of the partnership’s cash flow. However, as certain pre-determined distribution levels are met, the GP receives an incremental 15%, then 25%, and up to 50% of incremental cash flow. The purpose of the IDRs is to give the GP some “skin in the game” and incentivize the general partner to raise the quarterly cash distribution to reach higher tiers, which benefits the LP unitholders, as well.

Below is a typical IDR profit split arrangement:

Source: VTTI 10-K & Punchcard Calculations

There are significant flaws in this theory. The key issue is that the GP gets the lion’s share of upside potential without commensurate downside exposure. A general partner commonly owns a 2% stake in an MLP it manages. In a static scenario (i.e., one in which the distribution is not growing), the GP receives 2% of distributions, equal to its ownership stake. At worst, the GP’s 2% stake could become worthless. On the other hand, IDRs allow the GP to take home an increasing share of incremental distributions, while LPs receive a declining share. An MLP said to be in “high splits” typically pays 50% of its incremental distributions to the GP.

Martin Capital Management summed up the situation well:

“Any owner of a business must weigh the potential risks, or downside, of a business transaction against the potential gains, or upside. Shareholders in a business typically share proportionately in the downside and upside, and thus their interests are aligned in both direction and magnitude. For general partners in an MLP structure, however, the calculation of risk versus reward is very different than for limited partners. An acquisition that carries a potentially large upside now but an equally large downside in the future may be attractive when, for example, you can take home 70% of the gains but suffer only 30% of the losses. The opposite view of that deal – little upside now but a potentially large downside later – doesn’t quite have the same appeal! The GP may therefore be inclined to make risky decisions that are not in the LP’s best long-term interests or necessarily fair to all parties involved.”

The MLP Treadmill

Thus, we arrive at a situation where an incentive for risky growth is then combined with a reliance on outside funding. It is this dynamic that leads to the MLP Treadmill.

MLPs constantly need more capital to drive bigger and bigger deals so that they can keep growing distributions. In turn, bigger distributions will lead to a higher valuation. This is the MLP Treadmill. Once you get on and start feeding growth through external funding, it is very hard to stop and get off. And get off you must, eventually.

One of the inherent contradictions of the MLP model is that, if it works exactly as designed, the company will hit the high splits quickly. As the GP grabs a bigger and bigger piece of the pie, the cost of capital will increase commensurately. As one observer put it: ” The Company’s unit price depended upon constantly increasing dividend distribution, and ever-higher dividends, creating ever-greater IDRs, required staggering infusions of capital.”

For example, below is a look at the 20 year lifespan of an MLP. We have assumed a 7% yield at the outset with an expectation that the yield will grow by 3% per year. These assumptions give the MLP an initial cost of capital of 7%. But, by year 20, the GP is taking 4q% of distributable cash flow and the MLP must earn 51% on its equity to preserve the distribution growth to LPs. The universe of investments providing that sort of return is rather small.

Kinder Morgan serves as a cautionary tale. Kinder Morgan rode the MLP Treadmill all the way to its logical conclusion. From 1990 to December 1996, Richard Kinder served as the President and COO of Enron Corporation. He resigned from Enron in 1996 after being denied a promotion to CEO. He had a ‘headstrong belief in the profitability of collecting a toll to move energy through pipelines” which did not gibe with the more aggressive vision at Enron. After leaving Enron, he and college friend William V. Morgan started a pipeline business. They first purchased Enron Liquids Pipeline, a natural gas conduit business that Enron was eager to get rid of, for $40 million. They also merged with KN Energy. After a number of acquisitions, most prominently El Paso Corporation, Kinder Morgan became the largest midstream energy company in North America. Enron declared bankruptcy in 2002.

By 2014, the Kinder Morgan empire had greatly expanded.

Enron Liquids Pipeline evolved into Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP), a master limited partnership. KMP earned the majority of its income by transporting oil, natural gas and CO₂ through its approximately 52,000 miles of pipelines located throughout the United States and Canada. It also owns approximately 180 terminals dedicated to handling natural resources. The Company owns the physical pipelines, and collects lucrative fees when natural resource companies use those pipelines to transport their products. KMP had increased its dividend every quarter since its inception.

Combined, the Kinder Morgan family was the third largest energy company in North America, with an estimated combined enterprise value of ~$140 billion. Among other assets, the Kinder Morgan family owned the largest natural gas network in North America.

Yet on August 10, 2014, Kinder Morgan announced that it was shutting down its MLP and rolling them up into the main public company. Why would they do this?

By 2011, its MLP, Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP), was in the high splits. The GP was earning more than 50% of total distributions to unit holders. Further, over 100% of cash not needed immediately by the business was being distributed out. How much did this leave for growth investments? Not a whole lot:

Kinder Morgan Partners, Discretionary Cash Flows, 2011-2013

Source: Company filings via Sentieo.com

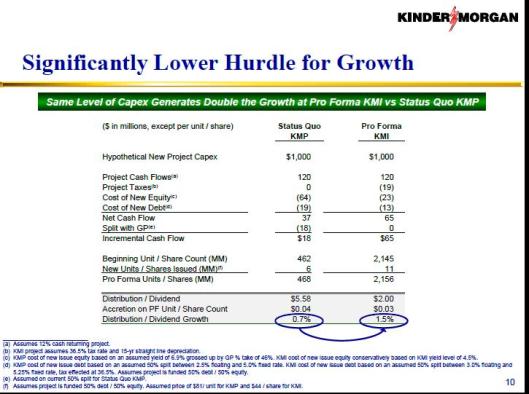

Further, with the GP in the high splits, the MLPs cost of capital was enormous and the corresponding hurdle rate for new investments severely limited the universe of accretive investments. Here is a slide from a Kinder Morgan investor presentation showing the return to minority unitholders and shareholders from a new investment in the MLP structure and in the more traditional corporate structure:

Kinder Morgan opted to hop off the MLP Treadmill rather than extend the pain. In 2014, they rolled up their MLPs into the Sponsor, effectively reversing years of drop downs.

Conflicts of Interest

When we take a minority position in publically traded companies, we always face the risk that the business is being run for the benefit of the majority owner and to the detriment of minority owners. However, this risk is dramatically heightened if none of the traditional protections for minority ownership are in place. Such is the case with MLPs

a. Fiduciary Duty Waived

As discussed above, MLPs are organized as limited partnerships rather than the more common corporation. MLPs take full advantage of the fact that Delaware law does not require GPs to act in the best interests of the LP. Therefore, as shocking as this sounds, the GP may act free of any duty or obligation to the MLP or its limited partners. For example, the PBFX 10-K states: “Our general partner and its affiliates, including PBF Energy, have conflicts of interest with us and limited fiduciary duties to us and our unitholders, and they may favor their own interests to the detriment of us and our other common unitholders.” (emphasis added) This provision alone is enough to scare us away from MLPs

b.IDRs Mean That Deals Can Be Accretive To The GP And Not The LP

The way IDRs are calculated makes it possible for actions to be taken that are accretive to the GP but not necessarily to existing LPs. Distributions paid to the GP are not based on the distribution per LP unit but the gross distribution to LPs. Therefore, even if the distribution per unit remains the same, the GP will receive a greater distribution. Here is a simplified example:

Notice that the equity funded acquisition, results in a 10% increase in the distribution to the GP while the LP remains the same.

c. Drop Downs Are Not At Arms-Length

Drop downs are often touted as a benefit of MLPs. For example, the amount of assets available for drop down by the Sponsor is used as a rough proxy for the future growth of the MLP. But, drop downs create a terrible conflict of interest. The buyer is merely an alter ego of the seller. How can a minority owner of the MLP have any assurance that both parties are negotiating a fair deal.

d. Lack of Voting Rights

Unlike common shareholders, MLP LPs have severely restricted voting rights and no vote for the board of directors. Further there is limited ability to remove the G

e. Call Rights

Another odd feature of MLPs are the call rights issued to the GP. These call rights allow the BP to acquire all of the common units held by the public at price calculated by partnership agreement but not less than the market price at the time. Therefore, LPs may be forced to sell when they don’t want to or when the price is artificially depressed.

Other Ways Management Can Rip You Off

Management has several other ways it can rip off the minority owners.

- Accounting Games

The most straightforward method management has to rip off investors is playing games with the numbers. As stated earlier, MLPs are required to distribute all available cash. However, all available cash is not a term defined under GAAP. This gives management significant leeway to pump up the numbers.

Below is a typical calculation of distributable cash flow by an MLP. It happens to be from ARCX but it could have been from any of them.

Source: ARCX 10-K

A couple of items stick out. First, the “one-time non-recurring” expenses sure do seem to recur a lot. But even more importantly, they are true expenses and a reduction to cash. Why are they being added back?

Second, “maintenance capital expenditures” is not a term defined under GAAP. This gives management a lot of leeway to play around with the numbers. Per the 10-K, management simply defines maintenance capital expenditures as “(i) clean, inspect and repair storage tanks; (ii) clean and paint tank exteriors; (iii) inspect and upgrade vapor recovery/combustion units; (iv) upgrade fire protection systems; (v) evaluate certain facilities regulatory programs; (vi) inspect and repair cathodic protection systems; (vii) inspect and repair tank infrastructure; and (viii) make other general facility repairs as required.” This last point is vague enough to cover (in good years) or not cover (in bad years) just about any capital expenditure.

Maintenance Capex, however, is intended to represent the cost inherent in maintaining the Company’s current capacity, and is generally funded from operating revenues. Because of that, expenditures classified as Maintenance Capex reduce the funds that may be distributed to the general partner and the unitholders. The GP has a powerful incentive to classify whatever expenses possible as Expansion Capex, as that leads to a larger payment for the GP.

Depreciation, depletion and amortization (“DD&A”) costs—reflective as they are of the anticipated expense of maintaining assets—should roughly mirror Maintenance Capex. Defying logic, the MLPs we looked at all had Maintenance Capex amounts far lower than their DD&A. In fact, the average ratio in 2015 was just 30%.

- Long Term Contracts can mask deteriorating economics.

One of the strengths of MLPs is there long-term contracts. This gives investors visibility far into the future and makes projecting future cash flows easier and more reliable. It also gives the business financial stability. But, long term contracts are a two-edged sword. Sure, it’s great to have the predictability, but when happens when the contract ends? Will the MLP be able to negotiate a renewal on same or better terms or will the customer walk away altogether? Long term contracts can paper over deteriorating economics until investors get a rude awakening. Particularly in a business as cyclical as oil and gas, future economics can look far different than the present.

- Midstream Companies Still have Commodity Exposure

While it is certainly true that midstream companies do not have direct exposure to commodity pricing, the commodity cycle still impacts their business. For example, storage businesses do better when forward prices are higher than current spot rates, a situation known as “contango.” Contango increases storage needs because oil companies know they get more money by waiting than by selling it immediately. The GP has fiduciary duty first and foremost to its own shareholders, not to the LPs. Because the GP has almost complete control of the MLP in any decision making process, the GP can maximize its own benefits ahead of or even to the detriment of the LP.

A Closer Look At WPT

While combing through the wreckage of the MLP sector, we did come across one company that looks pretty good, WPT:

- Current 8% yield and distribution has grown dramatically.

- Easy to understand. WPT’s sole activity is oil storage services.

- No direct commodity exposure since it does not take title to the oil it stores

- Unlike many MLPs, the GP does not have a 2% LP interest. The GP only earns income on the IDRs. It does not make money on the MQD.

- Sponsor provides just 38% of revenue reducing dependency on one customer.

- High ROIC

Most importantly, WPT management seems to reject the idea of hopping on the MLP Treadmill. It has never increased its distribution.[2] It has distributed the minimum quarterly dividend each quarter since going public in August 2013. Because the distribution has not grown, the company has not triggered any distributions on the IDRs. Further, it has not taken any debt to fund growth investments and has only participated in one dropdown transaction.

As one might expect, Wall Street is not happy about this. On the Q4 2014 conference, the following exchange took place:

Eric Wolff, Hawk Ridge Partners – Analyst [43]

I appreciate the conservative nature of the balance sheet. At the same time, I think your business is relatively stable, and one could argue that a very, very modest amount of debt, even if it’s just one or two times, is exceptionally safe, given the stability of the assets historically. What’s been the aversion to even taking on a modest amount of debt?

J.Q. Affleck, World Point Terminals, LP – VP and CFO [44]

Well, I think that’s kind of been a message from our Board that we do like operate in a very conservative nature. I think there’s a premium on having some flexibility in the business. As you’ve seen the capital markets kind of freeze up for MLPs, we feel like we’re in a very strong position to have the access to the funding through our debt facility as opposed to maybe being at that one or two times level that you speak of, and then having to access the capital markets if we wanted to maintain that ratio. So I think it’s just kind of the conservative and flexibility aspect that we’ve been looking at to provide that opportunity for us.

Nevertheless, an investment in WPT takes a lot of faith in management.

For example, the sponsor, Apex Oil Company, is not public. As a result, you must accept management’s assertions that they are doing just fine. For example, on the Q4 2015 conference call, the CFO stated: “Apex obviously does not disclose its financials, but it has done very well during the recent market conditions, and we consider them to be a very strong — very strong from a credit perspective. We’re not really in a position to disclose kind of their debt balances or any specifics with regard to their financials, but we don’t see them as posing any risk.”

Second, the Company has exercised a great deal of discretion in undertaking acquisitions. However, one of their stated objectives is to grow via third party deals. How long will they wait for their fat pitch? Will they get impatient and make a value-destroying acquisition?

Third, as described above, WPT and its competitors all assert that they have limited competition because of the unique location of their assets and the lack of suitable substitutes for competitors.

Nevertheless, on page 63 of the latest 10-K, WPT states: “Despite these barriers, there has been significant new construction of residual fuel storage facilities along the Gulf Coast in recent years, which we believe may account for some of the unutilized storage capacity at our Galveston terminal.” (Emphasis added.) We wrote to a member of the board of directors as well as Investor Relations seeking a reconciliation of this seeming contradiction. We received no response.

Any MLP’s management is at best a benevolent dictatorship. It has at its disposal all of the tools above. So far, WPT has simply chosen not to use them to a great extent.

When The Boring Is Made Exciting, Lookout!

When operating properly, midstream companies should be stable and boring. They are a utility-like business that should be valued like a utility. Not content with utility-like valuations, Wall Street attempted to make them more exciting. When Wall Street makes the boring look exciting, investors should hold on tight to their wallets.

As demonstrated above, the growth in distributions was not sustainable. But even with the drop in the price of oil and the collapse in valuations, MLPs are still unattractive due to the complicated structure and the poor incentives it creates.

[1] Another option is to reduce the quarterly dividend. Boardwalk Pipeline Partners did just that and saw its market capitalization drop by 50%.

[2] It’s odd to root for a stagnant distribution but such is the upside down world of MLPs.

Great article. Just a nit. You mixed up up the upstream and downstream definitions of oil and gas.

Thanks. I will fix it.

Some midstream MLPs (though perhaps not oil storage MLPs) have publicly traded GPs. Did you look at any of the publicly traded GPs?

Good question. I was intrigued by the idea. Sort of like owning the casino instead of being the sucker at the table. But, I did not look at any in any great detail.

and some bouth thier GP, like EPD and Magellan

some purchased their GP (like epd )

Thanks for the interesting analysis. Am I understanding this right in that the tiered IDR structure means that ROIIC to LPs face a massive hurdle? So as an LP you’re being promised growth when that’s actually the last thing you want?

Thats how I see it. Certainly, when the company hits the high splits, you would be better off with less growth.

Why don’t you go long the GPs then? Some are on the market. I know HITE hedge a firm that specializes in MLPs often does a pair trade long GP short LP.

I’m not saying its a bad idea. I just haven’t had time to look at it.

“MLPs are contractually required to distribute “all available cash.” ”

Not necessarily, and not (nearly) always.

If the partnership agreement between the GP and MLP requires the MLP to pay a distribution then it will abide by the agreement, unless the GP waives it, which it often does and especially if the MLP owns the GP.

As an example, BBEP has plenty of available cash but it’s suspended it’s distribution indefinitely as doing so would break loan covenants.

ARCX, to use your example, stated in it’s prospectus:

“We intend to make a minimum quarterly distribution of $0.3875 per unit ($1.5500 per

unit on an annualized basis) to the extent we have sufficient cash after establishment

of cash reserves and payment of fees and expenses, including payments to our general partner and its affiliates.

“Although it is our intent to distribute each quarter an amount at least equal to the

minimum quarterly distribution on all of our units, we are not obligated to make

distributions in that amount or at all.

“[and further} we do not have a legal or contractual obligation to pay quarterly distributions at our minimum quarterly distribution rate or at any other rate and there is no guarantee that we will pay distributions to our unitholders in any quarter.”

I could use examples from just about any MLP which would say the same thing.

I think you are missing both the forest and the trees.

The Trees

I think you are confused about the meaning of the term “all available cash.” The malleable definition of the word “available” gives the GP great discretion in determining how much cash is available.

As Latham & Wakins, a prominent law firm explained: “Most partnership agreements require the distribution of all available cash, but that determination is made after the general partner establishes reserves within its discretion. More specifically, “available cash” is commonly defined as all cash on hand during a quarter, less (a) reserves established by the general partner to provide for the proper operation of the business, (b) cash necessary to comply with debt covenants, (c) reserves necessary to provide for distributions for any of the next four quarters and (d) working capital borrowings after the end of a quarter. This definition clearly gives the general partner wide discretion. Nonetheless, because the MLP is traded based on a multiple of cash flow, the more assurance an investor has that he will receive cash distributions, the greater the market valuation. As a result, most MLPs have utilized some form of cash distribution support.”

But the example you cite is even simpler to understand. If BBEP is barred by loan convenants to distribute cash over a certain amount, such cash should fall in no one’s definition of “available.” Its not as if the GP waived the distribution out of the goodness of his/her heart. The GP was barred by contractual agreement with the bank from making the distribution.

The Forest

The GP has a strong incentive to use an expansive definition of “available.” They want to maximize the distribution to (1) pump up the value of the LP units and (2) get into the high splits as quickly as possible.

Moreover, even if they act sensibly and don’t mortgage the future by maximizing the current distribution, just have this discretion is inviting trouble.

Pingback: Some Links | valuetradeblog